Two Seat Kit Built Scorpion Helicopter

ARTICLE DATE: October 1979

FOR THE PRICE of a 10-year-old Cessna Skyhawk, how would you like to own an ultra-sharp, brand-new, go-anywhere, homebuilt, two-place Scorpion 133 helicopter, with a complete flight-training program leading to an FAA Private Rotorcraft Rating?

A custom-built beauty you can operate from your own backyard, one you assemble yourself and do all maintenance work on, to keep the cost down? A chopper you can fly for $6 45 an hour direct operating cost, about half that of a comparable commercial whirlybird?

We’re talking about B J Schramm’s latest model Scorpion 133, an ultimate transportation/recreational vehicle for the homebuilder who thought he had everything. It comes as a package deal that includes a $10 information kit for starters, then a $95 Helicopter Owner’s Indoctrination Course, complete with tape cassettes and color slides.

Then, once you’re satisfied that you want to be a rotorwing jock, you’ll receive complete construction packages, a new 133-hp RW-133 liquid-cooled powerplant and a complete training program that covers flight training, operation and theory, and maintenance ground school.

With all this and fun, too, Schramm seems to have made the most sensible approach to the wonderful world of rotorcraft building, flying, and ownership with the Scorpion 133 helicopter.

It should satisfy the need of the amateur constructor whose past experience has been limited to stiff-wingers, or maybe balloons. The Scorpion 133 helicopter is an evolutionary, not a revolutionary, whirlybird whose roots go deep.

Thirteen years ago, in 1966, B.J., a 28-year-old helicopter design engineer, introduced the Scorpion’s grandpa, an open-cockpit single-seat rotorcraft called the javelin; the next year he brought out a kit version, the Scorpion, named for one of those nasty, mean, ugly, little desert critters that have a tail stinger somewhat resembling the tail rotor assembly of a helicopter.

Whereas the desert scorpion is a loner and will try to kill and eat any other scorpion around, including her lover (the female is the dangerous one, remember?), B.J.’s Scorpion was a downright friendly machine, an open-framework aircraft for hover-lovers, though not much protection from the wind.

In 1970, when a two-cycle powerplant of 125 hp became available, the single-seater became a two-place Scorpion Too, with a gross weight of 1125 pounds Soon other aerodynamic and mechanical improvements were added to make Scorpion Too a practical, light utility rotorcraft.

One thing bothered B J… He had in mind a four-cycle reliable powerplant of the aircraft type, but none was available with enough power to haul two people in a machine with an empty weight just under 700 pounds, so he set out to design and build one himself.

From a concept in 1975, the RW-133 aircraft engine became a reality in two years and is now available for delivery.

The RW-133 looks a little like a VW engine, but has a water-cooled crankcase and cylinder heads, weighs 170 pounds dry, has a 133 cu in displacement (CID) and puts out the same horsepower at 4500 crankshaft rpm, with a specific fuel consumption of 4 pounds per horsepower per hour.

The RW-133 turned out so well in fact, that BJ modified it to deliver 100 hp at around 3500 rpm direct drive, to help fill the need for a good, low-cost ($3,600) engine for builders of conventional aircraft. At Oshkosh this summer, both were demonstrated.

By late 1976 B.J.’s company. RotorWay Aircraft Inc., of Tempe. Arizona, had renamed the Scorpion Too whirlybird Scorpion 133 in honor of its new engine. It also featured a new, asymmetrical airfoil rotor system to improve its efficiency.

In addition, a new marketing program was adopted, and today Scorpion 133 helicopter is available only as a construction package, direct from the factory, no middleman, although overseas distributors are available if you live outside the United States.

The RotorWay approach to helicopter design stresses a low initial cost of around $11 per pound compared with $50 per pound for the average turbine helicopter airframe Schramm has described the design of a helicopter as “essentially a series of vibrations, all of which are being made to function in harmony with one another.”

“Three major flywheel effects are present — the rotor-blade system, the tail-rotor system and the powerplant system. All must operate in perfect harmony to achieve smooth flight.”

New two-place Scorpion 133 homebuilt helicopter can be flown for only $6.45 per hour direct operating cost.

B J had to choose among three classic rotor-hub configurations for the Scorpion: the teetering or semirigid hub, the fully articulated hub and the completely rigid hub. He chose the first as best suited to the novice flyer, with a more rigid set of safety standards as well as the most economical configuration.

In a semirigid hub, he explains, the collective control changes the blade pitch relative to the hub. Cyclic pitch or directional control is achieved by tilting the rotor hub with respect to the main drive shaft.

In the Scorpion, cyclic and collective controls, rather than being mixed, are kept separate and distinct by tilting the hub only with the cyclic control and using a flexible push-pull cable for separate collective control.

This patented system was a sort of mechanical breakthrough. Equally important is the design of the Scorpion’s two rotor blades, built to withstand three kinds of forces:

-

A centrifugal force, due to tip speed and blade weight, of nearly 8000 pounds. This tremendous stress is transferred from blade to rotor hub with a series of fiberglass doublers

-

A torsional load of some 600 pounds applied to the main shaft, producing pitch instability in a blade without sufficient stiffness

-

Control forces, which must be identical to each blade when a movement of the cyclic control is made, to avoid severe cyclic stick feedback due to out-of-track operation.

The Scorpion 133 helicopter rotor system is designed to handle all these forces well, including a patented rotor blade using a D-section steel leading edge interlocked with a V-section aluminum trailing edge, bonded and screwed to a birch main spar, tough enough to behead a duck.

The Scorpion rotor system turns counter-clockwise, with the primary drive using belts for power-pulse damping. A series of three drive belts runs back to the tail rotor.

In operation, the Scorpion 133 helicopter pilot uses a twist-grip throttle to add or subtract power automatically as the collective pitch stick is moved, adding or subtracting pitch equally from each rotor blade for climbs and descents.

Directional movement is maintained with the cyclic control stick, which tilts the rotor disc in the direction the pilot wants to go, accelerating in proportion to the degree of tilt. Single or dual controls may be used.

The cabin enclosure is a streamlined fiberglass unit providing maximum visibility through a large windscreen, and is easily removable in a matter of minutes for repair. Its pretty shape is more than aesthetic — it actually adds miles per hour and improves flight stability due to its design.

Unique is RotorWay’s “Scorpion Sky Center” flight training facility, where you start off by attending an introductory seminar to learn what you’re getting into. Next comes a preconstruction ground school course, the first of a two-part assembly training program.

Flight training is covered in three phases, with considerable coordinated ground study using videotape presentations. You begin by studying FAR Parts 61 and 91, and then get the second half of your construction lessons.

Following 20 hours (or less) of hover flying near the ground, you start learning translational flight up through 45 mph speeds, and get signed off for solo flight over one of the local hover pads.

You can also take your toy home then, wind it up and play in your own backyard if you like, or stick around the Salt River Valley country (the local Chamber of Commerce now refers to it as the Valley of the Sun), and learn all about full climbout and approach techniques and autorotations.

After that you’re ready for a flight check, hopefully to win your FAA Private Rotorcraft rating. To take an a typical case, let’s look in on Malcolm K (Mike) Carpenter of Anderson, Indiana, who read about the Scorpion 133 helicopter and fell in love with it back in 1971.

New Blood For The Scorpion 133 Helicopter

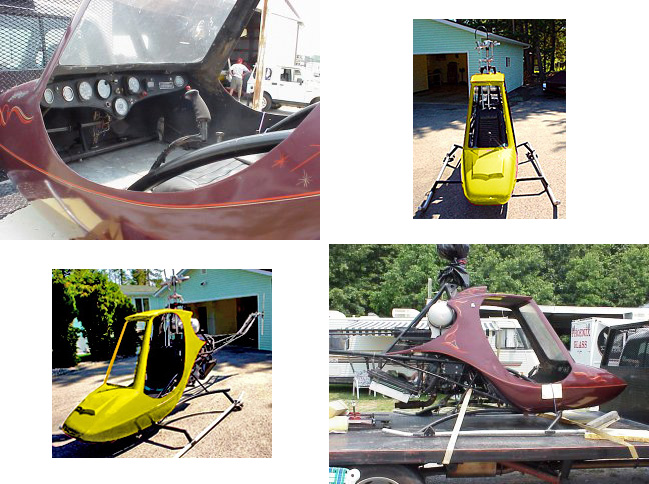

A buddy, Jack True, fell in love with the same beauty, and rather than create a triangular scene, they both bought kits. Both were top metal-workers, and things shaped up beautifully. In addition, Mike went the custom route and added a bigger instrument console and a completely enclosed cabin upholstered in red and black velvet — would you believe?

He also installed an alternator, two quartz landing lights, a 12.5-gallon fuel tank and a chrome-plated heat shield under the engine, so he can see its reflection. He had to make some changes to install the new RW-133 engine, and finally last summer towed the whirlybird to Oshkosh where it easily won the top Grand Champion Rotorcraft Award from the EAA.

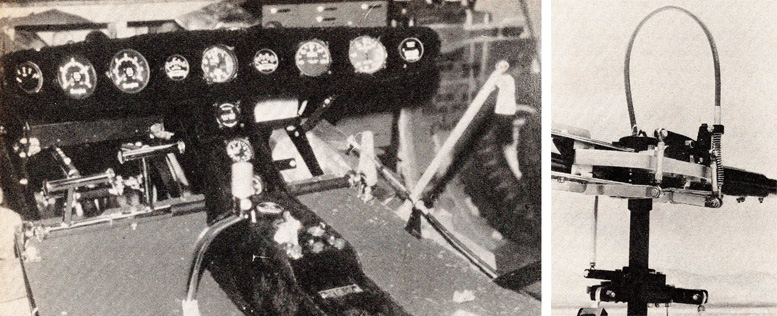

LEFT: Instrument console of Mike Carpenters prize-winning Scorpion homebuilt helicopter is covered with black velour “fur.”

RIGHT: Scorpion helicopter rotor system is teetering, semirigid type, flexible push-pull cable provides separate collective control.

Named Lil’ Susie for his patient wife, much of its attractiveness comes from a fantastic paint job of DuPont Centari enamel. The Scorpion 133 helicopter instrument panel, Mike designed is covered with black velour and is easily removable for servicing the gauges.

The dials in Mike’s bird include fuel gauge, rotor RPM, engine RPM, oil pressure, oil temperature, manifold pressure, engine-hours meter, altimeter, airspeed indicator, G-meter, clock, water temperature gauge and volt/ammeter.

There are also master and magneto switches, push-buttons for a strobe and two quartz landing lights, and beneath the panel a hot-water heater for winter flying. The alternator keeps the battery up; it’s almost a necessity, Mike says, as the battery won’t stand many start-ups without an APU.

There’s much chrome-plating on Mike’s Lil’ Susie, and the aluminum of the rotor hub, swash plate and tail rotor assemblies were spectacularly hand-polished. It was so pretty that Mike towed her down to Rockford for the International Popular Rotorcraft Association meet and won more prizes:

-

Best Customized Helicopter,

-

Best Detailed Workmanship,

-

Best Paint job and

-

Best Static Display.

That was all nice — but would it fly??? Last October Mike got it off the ground and went ground skimming. He recalls: “It gave me a great feeling at this point, and even at this very small altitude I knew my creation could leave the earth in the manner in which it was intended.”

Lousy weather moved in before Mike could complete his flight training and get into translational flight, but by now he’s well on his way as one of several hundred Scorpion pilots. (B.J. won’t say just how many, for proprietory reasons)

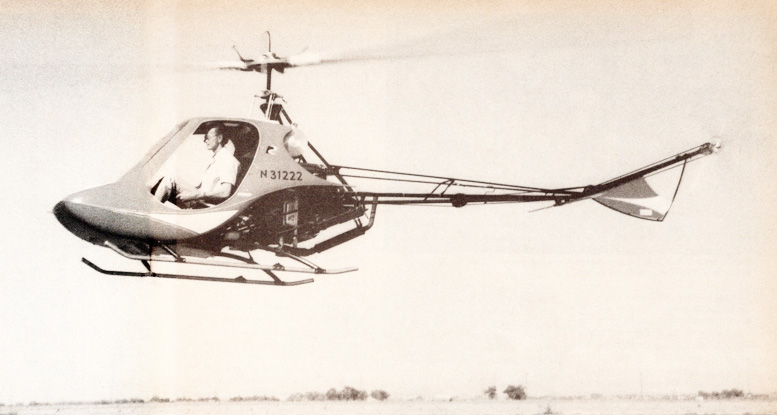

Early single-place Scorpion hovers over Moiave Desert as homebuilder gets in some rotorcraft practice.

For all the nice things you can say about the Scorpion 133 helicopter, it has not been entirely immune from accidents. In 1976, the NTSB reported four Scorpion accidents, including two fatals.

Last year the EAA reported five Scorpion mishaps, three resulting in minor injuries, the other two more serious. One of the latter, in fact, involved B.J. Schramm himself, who suffered a couple of broken ribs in a hard landing after his engine lost power.

His passenger was unhurt, and we are glad to report that B.J. is up and about again. And last March a Scorpion pilot in South Carolina was killed when his machine “just fell and crashed,” according to the EAA.

While RotorWay no longer sells plans for the Scorpion 133 helicopter, for $13,500 you get complete helicopter construction packages, one RW-133 four-cylinder water-cooled engine and a complete training program including flight training, operation and theory, and maintenance ground school.

| SCORPION 133 HELICOPTER SPECIFICATIONS & PERFORMANCE | |

|---|---|

| Main Rotor Span | 25 ft |

| Length | 20 ft 6 in |

| Height | 7 ft 3 in |

| Tail Rotor Span | 42 in |

| Seats | 2 |

| Empty Weight | 790 lbs |

| Gross Weight | 1220 lbs |

| Engine | RW 133 |

| Horsepower | 135 |

| C.I.D. (Cubic Inch Displacement) | 133 |

| S.F.C. (Specific Fuel Consumption) | 0.4 |

| Cooling | Water |

| RPM | 4500 |

| Vmax | 90 mph |

| Cruise | 80 mph |

| Climb | 800 fpm |

| Range | 120 miles |

| H.I.G.E. (Hover In Ground Effect) | 6500 ft |

| Service Ceiling | 10,000 ft |

| Useful Load | 420 lbs |

| D.O.C (Direct Operation Cost) | cents/mile |

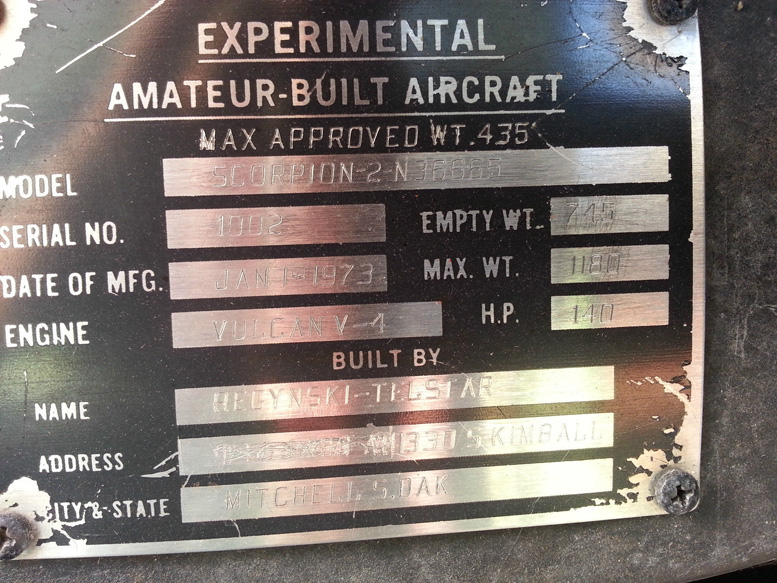

Hello

Thank you for your informative site.

I would like to build a Scorpion 133 and I need it’s plan, would you please send it to me.

Thank you

You are welcome, we will continue bringing you more in 2019. For the Scorpion 133, you need to Google Vortech Helicopters or Prizim Helicopters – I believe they now sell the plans and “some” parts.

I AM PLANNING TO PURCHASE A COMPLETED SCORPIAN 133. A/C ONLY HAS 23 HOURS ON ENGINE AND AIRFRAME. WOULD LIKE TO SEE IF ANY MAINTENANCE INSTRUCTION MANUAL IS AVAILABLE

I believe Vortech is selling these plans.

https://www.vortechonline.com/specials/