Moving To Rotary Wing

ARTICLE DATE: May 1998

There is a common belief that it takes superior skill to become a helicopter pilot. Have you heard the myth that flying a helicopter is like rubbing your belly in a circular motion while tapping your head and balancing on one foot.. .in the dark?

Sure, there’s no question that there isn’t a football field large enough to contain your first attempts at hovering—and that helicopters are so unstable that they make aerobatic aircraft feel as solid as an airliner.

To put this in perspective, can you remember the first time you drove a standard-shift car or your first attempts at crosswind landings or those first fum bling efforts with the opposite sex?

You Can Get There

Just as you developed these “skills” with practice, so do student helicopter pilots. Every hour of instruction allows the student to make quantum leaps, and in about the same amount of time it takes to reach solo in a fixed-wing, you will be thrashing the air into submission on your own as you accomplish maneuvers that fixed-wing pilots can only dream of.

Fixed-Wing Knowledge and Helicopters

Another common fable holds that fixed-wing pilots must “unlearn” their airplane flying skills because helicopter handling is completely different. Although there is some truth to this concept, pilots should realize there is a great storehouse of knowledge gained during fixed-wing operations that are equally useful for helicopter operations. For example, weather phenomena don’t change just because a set of helicopter blades are beating at the air.

In fact, the helicopter’s ability to maneuver at low speed and turn in an extremely short radius allows the helicopter to tackle weather that is well beyond the capabilities of a pilot in an airplane. Besides, if you don’t like the weather, a helicopter will give you the opportunity to land almost anywhere and wait for better conditions.

Navigation knowledge is also very similar, except you won’t be able to take your hands off the controls to refold the chart, and your vision won’t be blocked by wings and a large engine cowling. Then there’s aerodynamics. Because they are essentially the same for helicopters, you won’t have to learn much about lift, drag, weight and thrust.

Before flying a single-seater such as the Mini 500, you will need instruction in a trainer such as the Robinson R-22 or Schweizer 300.

But there are a few differences in the way controls affect these aerodynamic changes. Once the helicopter gets up to 40 mph or so, the effect of the aft-mounted fins and stabilizers greatly reduces the flying work load. Moreover, the cyclic, which looks much like a joystick, also works like a joystick in cruising flight.

So what’s the big challenge? Basically it’s hovering. A fixed-wing pilot attempting his first hover will feel like he is trying to stand stationary on top of a beach ball—one that’s floating in the ocean.

In effect, a high-pressure bubble of air compressed between the rotor blades and the ground provides a very shaky cushion of moving air that accentuates every control movement, turning a small correction into a massive and ever-increasing deviation away from the desired spot.

Add a gusting wind to the equation and initial hovering attempts look more like a cross-country flight with no fixed direction. Just as that combination of shifting gears and letting out the clutch while attempting to maintain direction seemed impossible at first, in short order, our attempts to control a hovering helicopter begin to show success.

What about Autorotations?

While it’s true that landing a helicopter after an engine failure is similar to dead sticking an airliner into a farm field, it’s a skill that once mastered gives the helicopter pilot the ability to turn a powertrain failure into nothing more than a landing at an unplanned destination.

For those would-be rotor heads who are a little bit scared about the risks involved in helicopter flying, you will learn that—as in automobiles—speed kills. Because helicopters are capable of reducing impact speeds during emergency landings, pilots and passengers are twice as likely to avoid serious injury during impacts compared to fixed-wing aircraft.

Moreover, the helicopter’s ability to reduce speed without the risk of stalling allows pilots a vast safety margin when operating under conditions of reduced visibility such as fog and smoke. As a result, helicopters are permitted to fly in lower weather minimums than airplanes.

The Hard Part

Although rotary-wing ground school has some new mental challenges—and the initial flight training attempts at hovering seem nigh impossible—it all starts to work out after a few hours. The biggest challenge for most would-be fling-wing pilots is finding enough money to complete the training program.

Many pilots are not able to meet the government standards within the minimum published flight time; most students require anywhere from a few hours to dozens of hours of extra dual training to pass the flight test.

If you run out of money when you reach the basic minimum flight hours and you aren’t ready for your checkride, you won’t be able to complete your course. Be sure to have an extra stash of cash just in case.

The Cost $$$

In a word, lots! But the freedom of flight enjoyed only by birds and helicopters is well worth it. In Canada, a pilot with a fixed-wing pilot’s license can take a 30-hour course to gain a helicopter rating, but plan on at least 45 hours to meet the flight test standards.

A Canadian with no pilot license must take the 45-hour minimum course, but once again, you should budget for at least 50 hours of training at approximately $200 per hour (more in Canada) in a helicopter such as a Robinson R-22.

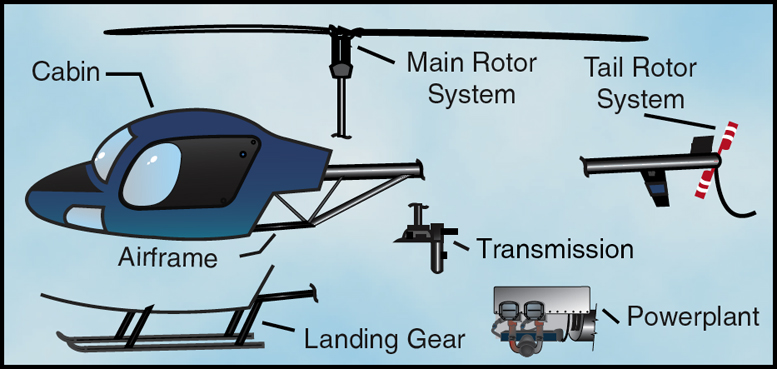

Helicopter pilots—especially those who will maintain their own machines—need a good understanding of every system such as this Revolution Helicopter Mini 500 transmission and rotor hub.

In the U.S., a pilot with an airplane license can take an abbreviated helicopter course comprised of 20 hours of dual and 10 of solo. For the unlicensed beginner, the requirement is 20 hours of dual and 20 hours of solo plus ground school.

To ensure you aren’t one of the many pilots who fail to complete the course due to financial failure, be aware that the basic course is quoted in the $8000 range for 40 hours of R-22 training; however, the average flight time for students is 72 hours! All of the additional hours will add considerably to the bottom line.

Incidentally, a reciprocal agreement between Canada and the U.S. will grant a pilot the other country’s license based on a pilot certificate/license from your own country.

But if you want to fly your homebuilt helicopter across the border you will need to apply to the other country’s aviation agency for a temporary approval with a maximum validity of six months.

Training Cloud with a Silver Lining

RotorWay International, producer of the Exec series of two-place helicopters, offers its own government-approved training package for owners of RotorWay helicopters regardless of vintage.

Company President and well-respected FAA flight examiner “Stretch” Wolter provided the details of RotorWay’s training. It is conducted over three phases using a company RW 162F for the 20 hours of dual and the customer’s own helicopter back at his home base for the solo requirement. The package includes ground school and is priced at $3800.

Because RotorWay does not conduct night operations, students will be required to buy three hours of dual training elsewhere to meet the night flying requirements for the U.S. license. As a helicopter instructor myself, I strongly recommend this syllabus for RotorWay helicopter owners for numerous reasons.

Trainees will learn to fly in the type of helicopter they will be flying. And because the differences between helicopters tend to be more pronounced than between fixed wings, experience in type is extremely important during the flight challenges typically experienced by low-time pilots.

Also, a RotorWay student will learn a great deal about production and maintenance on the Exec — knowledge of great importance for the builder who will perform his own inspections and repairs. Moreover, the student will be con ducting the solo portions of his training in his own helicopter, vastly reducing the training expenses while developing familiarity with his handiwork.

An additional benefit is saving time. RotorWay’s phased course only requires two and a half weeks on site compared to a typical helicopter course of 4-6 weeks minimum. I suggest training during the winter when temperatures in Phoenix are attractive compared to northern climes. Contact RotorWay for details (RotorWay’s flight school is at its factory in Chandler, Arizona)

Choosing a School

While a school’s location and facilities may be important, you will do well to find a school known for the quality of its graduates. Typically, these schools have experienced instructors with lots of field experience and the highest instructor ratings. It also helps if they are strictly a training operation so your helicopter isn’t out on a charter flight when you arrive for a lesson.

Also, having more than one helicopter in the inventory is beneficial so instruction doesn’t grind to a halt during downtime. Also, look for a detailed helicopter ground school (not a modified fixed-wing course) that will pass on as much inexpensive knowledge as possible. Too many schools skimp in the classroom, making flight training a longer, more expensive ordeal.

Choosing a Type

There are a lot of piston helicopters available for training: Robinson R-22, Hughes/Schweizer 300 series, Bell 47, Hiller 12E and the Enstrom series, to name a few. Because you may someday choose to trade your kitbuilt machine for a factory-built helicopter that flies farther, faster and carries more payload, it might be wise to train in a machine you may someday be able to afford. Therefore, I recommend the R-22 and 300 CB variant as not only the least expensive to train in but also the cheapest to operate when all factors are considered.

Learn in Your Own Kit Helicopter?

While this dream can become reality, there are some stumbling blocks. First, if your machine is single-seat, dual instruction isn’t possible. You could take your dual training in a certified helicopter, but your instructor would have to cooperate and sign you off to fly your single-seat machine. Many CFIs will be reluctant to do this.

Also, flying an R-22 during the 8 hours or so of dual instruction and then switching to your very light homebuilt for your first solo is more of a challenge than most people need. You should fly at least the first few solo hours in the two-seat training machine.

For those planning to follow this route, you need to find an instructor who is prepared to instruct you in your home built and a flight examiner who consents to conduct your flight test in your homebuilt—and many won’t. Perhaps part of your course will be educating an instructor on the benefits and quality of homebuilt helicopters.

Whatever route you choose, a rotary-wing license grants entry into extended challenges and pleasures not available to the “seized-rotor” folks. Coupled with the growing number of kit helicopters expanding your choices for freedom, the sky is no longer the limit.

Be the first to comment on "How tough is the transition to helicopters"